In the run-up to the 15th United Nations Conference on Biodiversity, several States have committed to creating protected areas on at least 30% of their land and sea territories by 2030. This tendency to focus on the proportion of land and sea to be protected in order to preserve biodiversity obscures more fundamental questions: how conservation is done, by whom and with what outcomes. These questions are crucial for effective biodiversity conservation.

Lead author, Dr Neil Dawson of University of East Anglia (UEA) School of International Development, was part of an international team conducting a systematic review that found conservation success is “the exception rather than the rule” – but research suggests the answer could be equitable conservation, which empowers and supports the environmental stewardship of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. This global review of evidence takes advantage of a growing number of studies looking at how governance – the arrangements and decision making behind conservation efforts – affects both nature and the well-being of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

The work is part of the JustConservation research project funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) within its Centre for Biodiversity Synthesis and Analysis (CESAB), and was initiated through the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy (IUCN CEESP). It is the result of collaboration between 17 scientists, including researchers from the European School of Political and Social Sciences (ESPOL) at the Catholic University of Lille and the University of East Anglia. The findings are published on 02/09/2021 in the journal Ecology and Society.

Dr Dawson said: “This study shows it is time to focus on who conserves nature and how, instead of what percentage of the Earth to fence off. Conservation led by Indigenous Peoples and local communities, based on their own knowledge and tenure systems, is far more likely to deliver positive outcomes for nature. In fact, conservation very often fails because it excludes and undervalues local knowledge and this often infringes on rights and cultural diversity along the way.”

International conservation organisations and governments often lead the charge on conservation projects, excluding or controlling local practices, most prominently through strict protected areas. The study recommends Indigenous Peoples and local communities need to be at the helm of conservation efforts, with appropriate support from outside, including policies and laws that recognise their knowledge systems. “Furthermore, it is imperative to shift to this approach without delay” Dr Dawson said. “Current policy negotiations, especially the forthcoming UN climate and biodiversity summits, must embrace and be accountable for ensuring the central role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in mainstream climate and conservation programs. Otherwise, they will likely set in stone another decade of well-meaning practices that result in both ecological decline and social harms. Whether for tiger reserves in India, coastal communities in Brazil or wildflower meadows in the UK, the evidence shows that the same basis for successful conservation through stewardship holds true. Currently, this is not the way mainstream conservation efforts work.”

From an initial pool of over 3,000 publications, 169 were found to provide detailed evidence of both the social and ecological sides of conservation. Strikingly, the authors found that 56 per cent of the studies investigating conservation under ‘local’ control reported positive outcomes for both human well-being and conservation. For ‘externally’ controlled conservation, only 16 per cent reported positive outcomes and more than a third of cases resulted in ineffective conservation and negative social outcomes, in large part due to the conflicts arising with local communities.

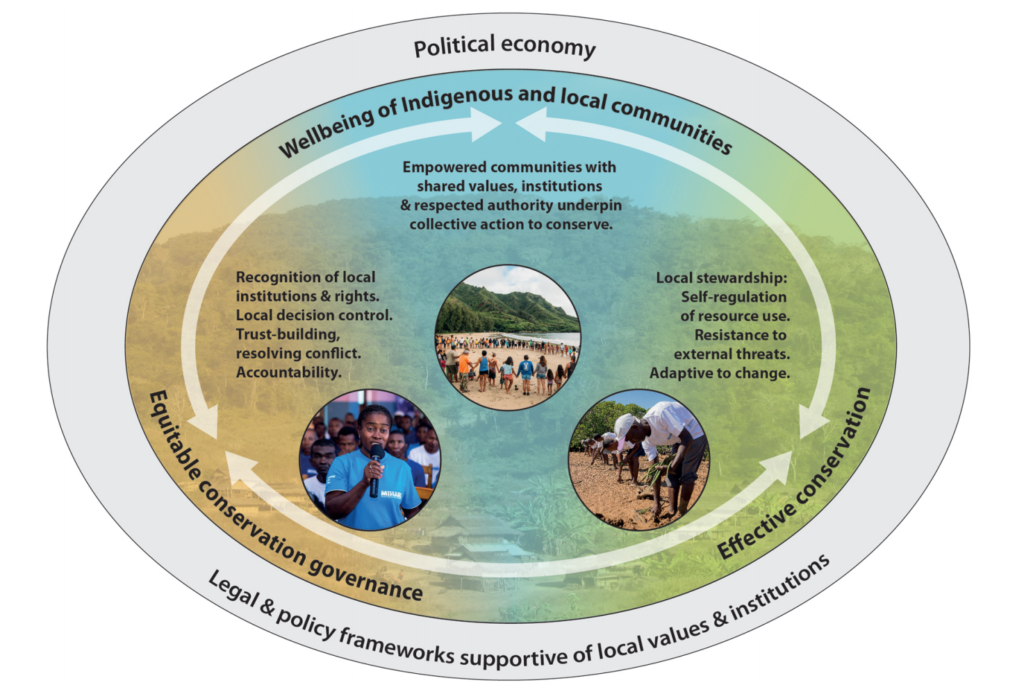

However, simply granting control to local communities does not automatically guarantee conservation success. Local institutions are every bit as complex as the ecosystems they govern, and this review highlights that a number of factors must align to realize successful stewardship. Community cohesion, shared knowledge and values, social inclusion, effective leadership and legitimate authority are important ingredients that are often disrupted through processes of globalisation, modernisation or insecurity, and can take many years to re-establish. Additionally, factors beyond the local community can greatly impede local stewardship, such as laws and policies that discriminate against local customs and systems in favour of commercial activities. Moving towards more equitable and effective conservation can therefore be seen as a continuous and collaborative process.

Dr Dawson said: “Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ knowledge systems and actions are the main resource that can generate successful conservation. To try to override them is counterproductive, but it continues, and the current international policy negotiations and resulting pledges to greatly increase the global area of land and sea set aside for conservation are neglecting this key point. Conservation strategies need to change, to recognize that the most important factor in achieving positive conservation outcomes is not the level of restrictions or magnitude of benefits provided to local communities, but rather recognising local cultural practices and decision-making. It is imperative to shift now towards an era of conservation through stewardship.”

Figure: The central and inseparable role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in equitable and effective biodiversity conservation

![[Press release] Stewardship by Indigenous and local communities is the key to successful nature conservation](https://www.fondationbiodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/CP_JustConservation_Web.jpg)

![[Press release] A better protection of marine megafauna through social networks and artificial intelligence](https://www.fondationbiodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Dugong©Julien-Willem.-Wikimedia-commons_web.jpeg)

![[Press release] Study in Nature: Protecting the Ocean Delivers a Comprehensive Solution for Climate, Fishing and Biodiversity](https://www.fondationbiodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Photo_CP_web.png)